How do you work out logarithm tables

In 1614 (yes 1614) John Napier produced a work of natural logarithm tables. The paper contained ninety pages of tables and fifty seven pages of explanatory notes.

This took him 20 years to create.

Then Henry Briggs changed these original logarithms into a common (base 10) logarithm. The method John Napier used was extraordinarily long winded.

Can we find any logarithms ourselves without Napier?

Because logs are in reverse it’s actually easier to find some anti logarithm numbers using iteration.

Logs – Napier – Briggs

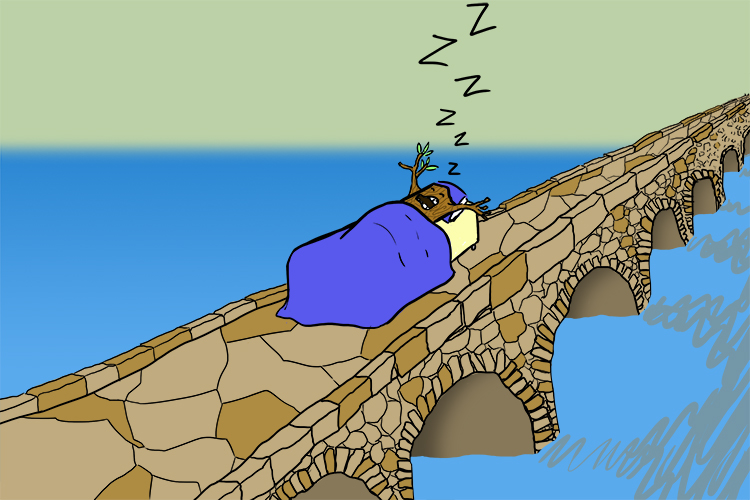

To remember the connection between these people think of the following picture:

The log took a nap here (Napier) on the bridge (Briggs).

Logs – Nappier – Briggs

Example 1

We know `9^0.5=9^(1/2)=root(2)(9)`

Which all really mean that:

What can you multiply twice to get `9`

(the answer is `3` (i.e. `3xx3=9`))

Using the same logic then

`10^0.1=10^(1/10)=root(10)(10)`

and this means that:

What can you multiply ten times to get `10` ?

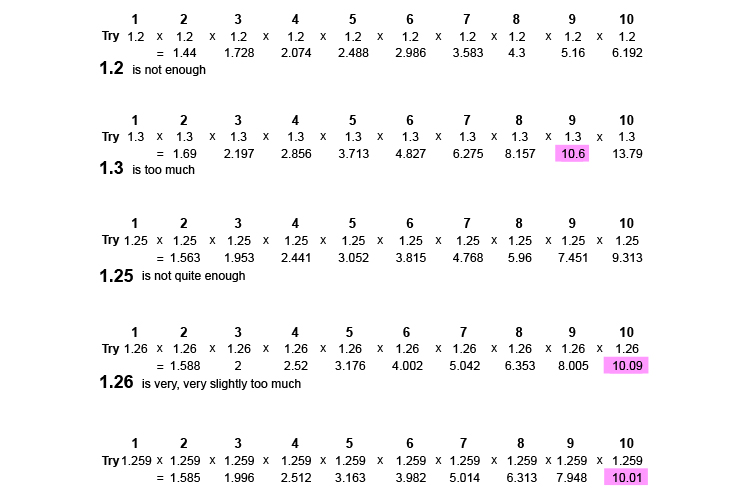

We can attempt to find this by trying different values. Try multiplying `1.2` ten times and see if we get close to a value of `10`.

If that doesn't work, add a bit on and try `1.3` as follows.

What do we have to multiply by itself ten times to get `10` ?

But this is very long-winded.

NOTE:

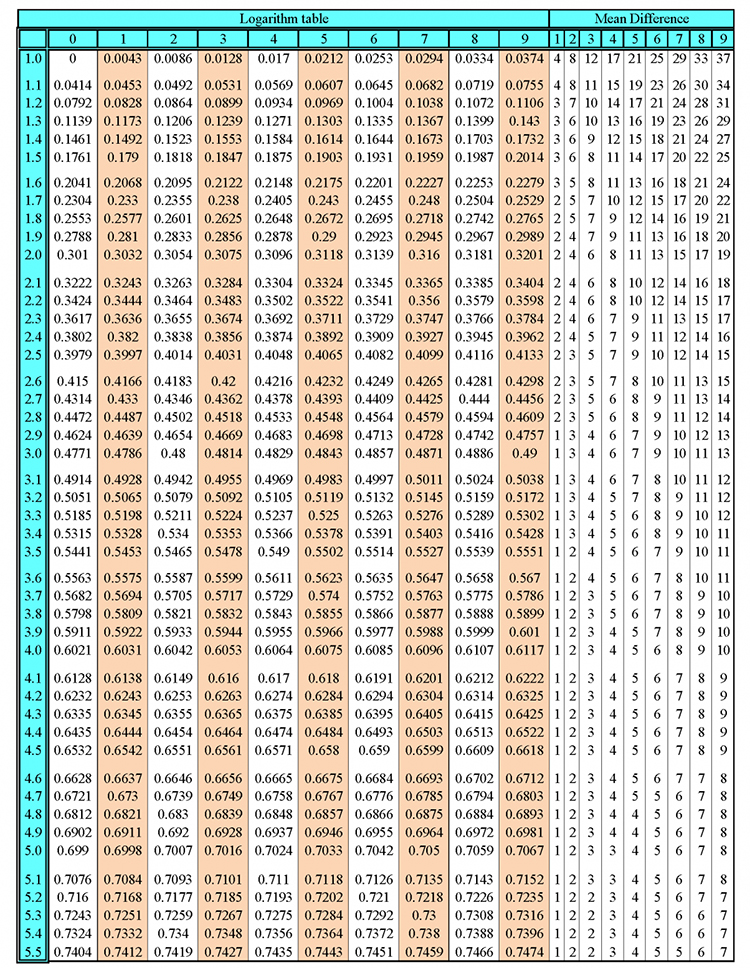

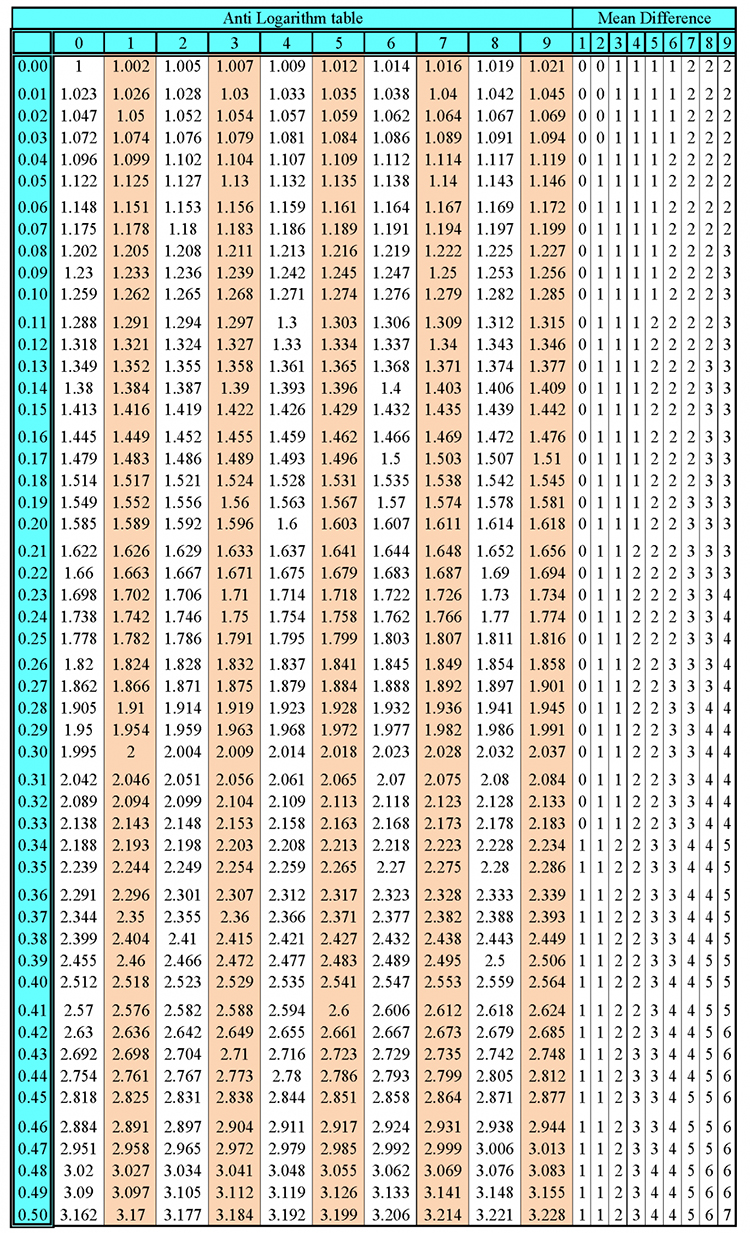

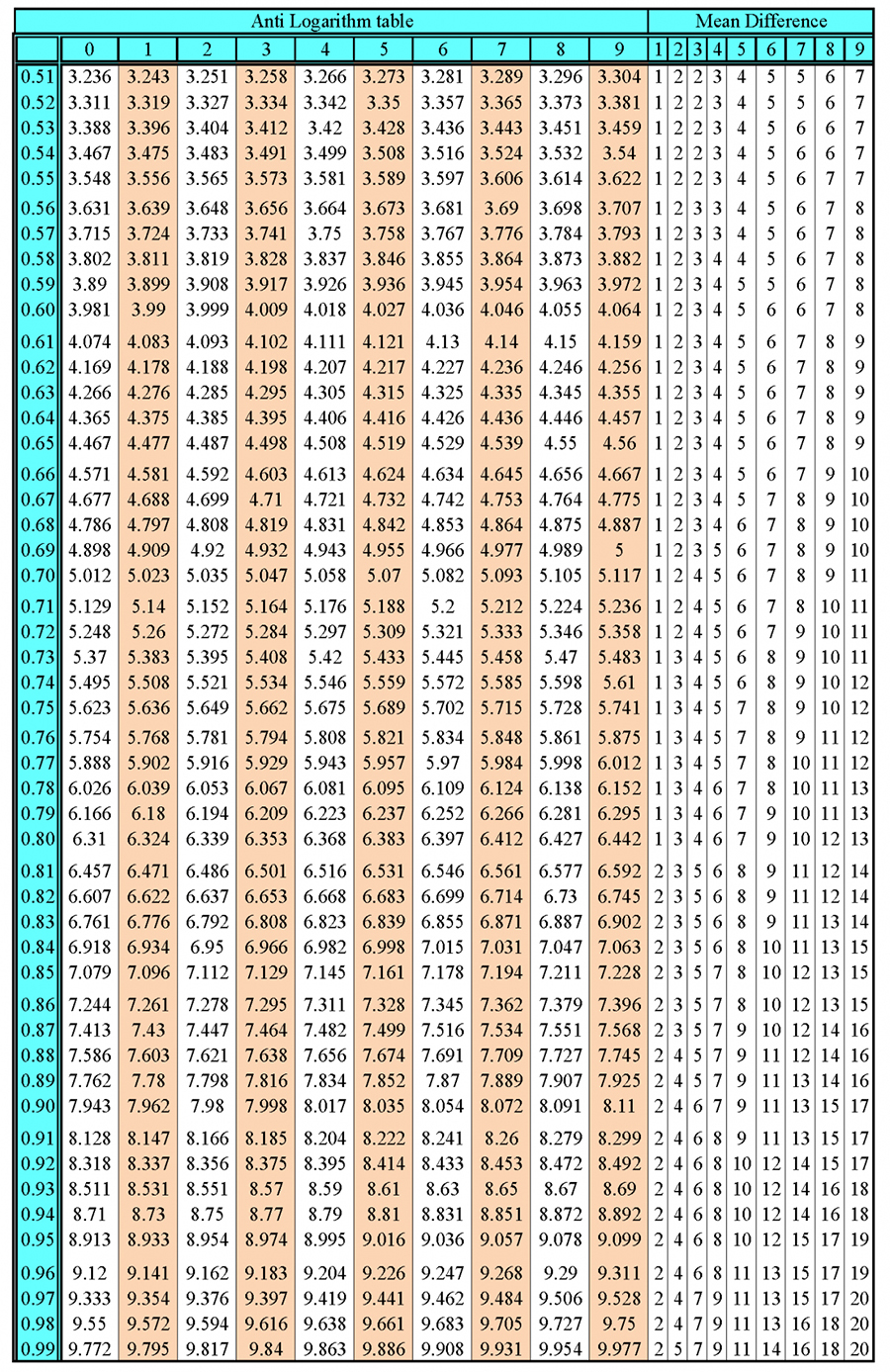

Using antilog tables for `10^0.1` antilog of `0.1 = 1.259`

Example 2

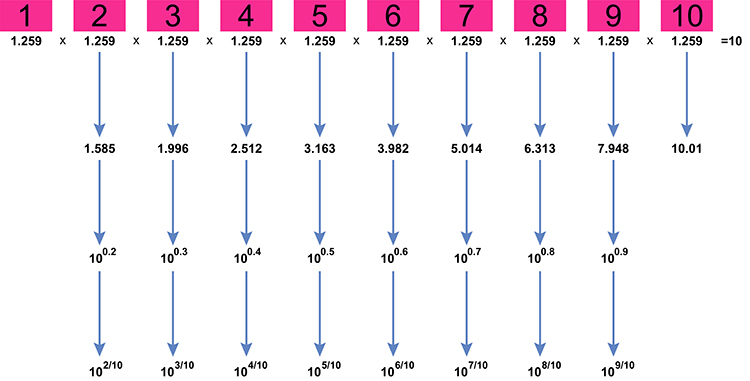

Now that we know that `10^(1/10)=1.259`

To work out the antilog of each of the following:

`10^0.2`, `10^0.3`, `10^0.4`, `10^0.5`, `10^0.6`, `10^0.7`, `10^0.8` and `10^0.9`

Is easy because we can turn these all into fractions `10^0.2 = 10^(2/10)`

`10^0.2 = (root(10)(10))^2`

Which means work out what we multiply by itself `10` times to get `10` (we know this equals `1.259`) and then multiply this answer by itself i.e. `1.259\times 1.259` .

`1.259\times 1.259 =1.585`

Double check using antilog tables.

`10^0.2` = antilog of `0.2 = 1.585`

So as follows the rest would be