Immunity

After an infection, “memory” lymphocytes are produced and remain in your body for many years – so you are protected against a pathogen.

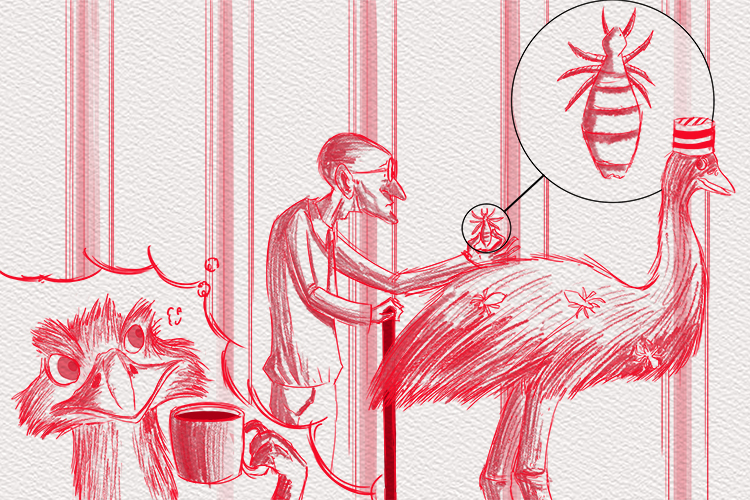

An emu with nits, drinking a cup of tea (immunity), has a memory of the time she had her own jailer with a limp and poor eyesight (lymphocyte) who used to pick the nits from her feathers.

Acquired immunity

Also referred to as acquired active immunity, or just active immunity, this type of immunity is developed after infection by a pathogen.

A choir of emus that have nits and drink tea (acquired immunity) didn’t get the choirmaster’s cold because they’d had that particular variety before, and so were immune.

Passive immunity

Short-term immunity provided by antibodies that come from outside the body – from another person or animal.

An emu with nits is passed through a sieve (passive immunity). It only stays there for a short term as it soon leaks out through the holes.

Examples of passive immunity

In natural passive immunity, antibodies are transferred to an unborn child through the mother’s placenta. These antibodies remain with the child for a few weeks after birth, providing passive immunity. If the baby is breast fed, it will have passive immunity for longer, as antibodies continue to be passed on through the milk. However, no “memory cells” are produced, so this type of immunity eventually runs out.

Breast feeding ensures babies have natural passive immunity for longer.

Passive immunity can also be obtained artificially, when high levels of antibodies to fight off a pathogen or toxin (obtained from humans or animals) are transferred to a non-immune person through blood products that contain antibodies.